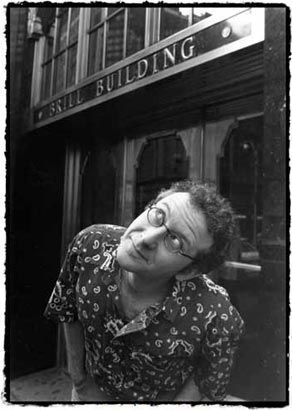

An interview with

Brian Woodbury

----------------

By

Beppe Colli

June

11, 2004

As

I recently wrote in my review of the album Variety Orchestra, it had been

since 1992 - the year when I first listened to an album featuring vivacious

and intelligent songs titled Brian

Woodbury And His Popular Music Group - that I had lost all traces of Brian

Woodbury, an artist whose music, so simple on first listening, revealed in

time quite a complex compositional logic.

Having in my

hands the newly-released CD Variety Orchestra was for me a double surprise:

first, because I had found Woodbury again; then, because this new - and excellent

- album featuring for the most part instrumental tracks was a big departure

from the Woodbury I knew. A Web search confirmed to me that this was an artist

with a varied background.

I thought of

doing an interview. Woodbury kindly agreed, so we had an e-mail conversation

between the end of May and the start of June. And here it is.

I've read that you started performing at the age of 11. Please,

tell me about the way you started developing an interest for music.

In much the usual way, at 3 or 4 I started messing around with my

parents' piano. I had the notion that if I put coins in between the

cracks, it would play like a juke box or a player piano (which I had

seen in an amusement park). My first experiments were attempts to evoke

soldiers and angels (the low end versus the high end).

I was always fascinated with recordings of Mozart's Don Giovanni

and The Beggar's Opera, as much for the swashbuckling swordplay as for

anything else. When I was five I organized plays at school that involved

swashbuckling heroes rescuing damsels in distress. I was always the

hero.

The usual experience - the Beatles during grammar school; started

writing songs on guitar at about 10 and performing a little later; listening

to singer-songwriters in my early teens; progressive rock in high school;

Zappa, Beefheart; modern classical; musical theater in college.

I know that you studied with Tom Lehrer. I've heard of him, but

I've never heard his music. (I read an interview with him by Paul Zollo

from 1990, one that Zollo later included in his Songwriters On Songwriting

book collection.) Would you mind talking about Lehrer - and about how

this experience was important for you?

Tom Lehrer was a revelation to me in high school. His songs had all

the craft of the Broadway greats combined with an acerbic and almost

subversive quality and none of the sentimentality (an attitude which

as a teenager I really related to). Also he was a brilliant, but understated,

pastiche artist.

I discovered to my delight that he taught at the college I went to

(University of California Santa Cruz). His class was called Introduction

to Musical Theater. One had to audition to get into it. So I got up

the courage to sing a song of my own for the audition. It was a Johnny

Cash satire that I had written in high school (Them Prison Gates are

a-Tumblin' Down).

The class consisted of one week of studies, alternating with a week

in which we would put together an abbreviated reading of a classic Broadway

musical from each of the major eras (20s through the 60s). It was a

terrific class.

During the class we got to know him well, and I started bringing

him some of the songs I was writing, to get his advice about songwriting,

particularly lyrics. Major influence on me, both before meeting him

and after.

You've collaborated with Van Dyke Parks - who has expressed admiration

for your work. Would you mind talking about this collaboration?

In 1983, my wife Elma Mayer and I were in a band called Some Philharmonic,

something that had come together at music school inspired by punk rock,

Parliament Funkadelic, Beefheart and Henry Cow. We found Van Dyke Parks's

Song Cycle in a used record store. I already knew it and loved it, but

the band hadn't. We went through an enormous phase of absorbing that

album over many months.

Elma discovered that Van Dyke lived in Los Angeles. She looked his

address up in the phone book and just decided to send him our LP. He

got it and listened to it and called us up on the phone. When he first

called my reaction was "bullshit." I thought someone was pulling

our leg. You might as well have said, "It's Abraham Lincoln on

the phone."

Later we moved to Los Angeles, Van Dyke tried to help us get a record

deal, which never happened. But we are still in touch and I am a great

admirer of his work. He has not received the recognition he deserves.

Has the recorded work of Brian Wilson been inspirational for you?

By the way, Wilson recently brought his Pet Sounds and Smile projects

to the stage for the first time. Did you have the chance to attend those

concerts?

But of course, this is a big influence. I think I spent about half

of 1985 and 1986 listening to Pet Sounds (the other half listening to

Cupid and Psyche 1985 by Scritti Politti). I have not seen any of the

concerts. I plan to if I get the opportunity.

When I first listened to your 1992 album of songs, Brian Woodbury

And His Popular Music Group, I seemed to notice a lot of musical references

being made (and: is it just my imagination, or do you really make a

verbal joke about a song by Elton John in Dreamstate Of California?).

It seems to me that this compositional strategy (i.e., referring, quoting,

in music) is nowadays quite less common than in the past. Your opinion?

This is a very good question, and I think you are right. Yes, there

is a reference to Your Song.

I made a conscious decision to avoid using references starting about

1995. I don't say never, but I think it can be a crutch. It is also

possibly distancing emotionally. Not for every listener, but for a lot

of people, humor takes the empathy. For me, I find humor in the face

of tragedy enriching, but maybe I'm just perverse. Anyhow, I've limited

the number of references for a while, particularly if the song is really

trying to convey something sad or serious. If you are writing for a

character who is not yourself, for instance in theater or children's

television, the character shouldn't make a literary reference that he

or she wouldn't get.

That notwithstanding, I read recently a new book has come out about

Shakespeare, cataloging all the references he made to the pop songs of the day. Many lines

in the plays refer to things that are hopelessly obscure, but were clever

allusions in their day. So I figure if Shakespeare could do it, what

the heck, lighten up.

I know you have a CD out called The Brian Woodbury Songbook, which

I've never listened to. Is it aesthetically different from the Brian

Woodbury And His Popular Music Group album?

A little more serious, less irreverent. Part of the reason I had

other people sing these songs, is I didn't want people to think they

were funny. A lot of time when I sing a song, people think it's funny,

even if it's about somebody dying. I guess I have someone of a comic

persona.

I'll send you one. You tell me.

In the booklet cover of your recent album Variety Orchestra you

mention the names of Carla Bley, Oregon, Henry Threadgill and Fred Frith

as musicians being inspirational for you. Would you mind talking about

this?

Until I wrote this music, I had been a songwriter, and never written

instrumentals. I'm not much of an instrumentalist myself, although I

do play guitar and bass, but I admire great instrumentalists, and there

was a huge amount of talent where I was living in the downtown New York

scene in the late 1980s, experimental jazz, etc. Since I'm not a great

player, I don't improvise much, and I tend to think more compositionally.

So as far as inspiration, I speak mostly of Fred Frith as a composer,

though he is a phenomenal improviser. His Gravity and Speechless albums

really opened up worlds for me.

Oregon (I forgot I mentioned them) again were amazing group improvisers

and I really dug that about them. And my bandmates and I used to do

some extended improvisation (never live), inspired by their approach.

But I guess for the record, they were an inspiration in terms of creating

a unique ensemble with a new palette.

Henry Threadgill I just think is great, and iconoclastic.

I think the CD actually is closest in spirit and sound to Carla Bley,

whom I first saw in 1980 in a little bar in San Francisco. I sent her

a demo tape and she wrote nice things back.

You've also written for theater, dance and television, and I know

you're a principal songwriter for Jim Henson’s Bear In The Big

Blue House. Please, talk about the different requirements this dimension

needs when compared to the other - is the word "stand-alone"

ok? - kind of songwriting.

Well, for the TV shows I wrote for, many of the songs were character

songs, in that they took place in a scene and were sung by a particular

character. So they were essentially theater songs. Theater songs you

try to get the voice of a character and the mood of the scene into song.

Is the person getting excited, calming himself down, motivating himself

to take a decisive action. It's all rather corny and formulaic if you

look at it in one way, but it's universal and profound. I'm a big sucker

for it.

Most of the other TV songs were more general and full of gentle admonitions

or revelations, sung in an avuncular way. Since I often write that kind

of song, it was right up my alley.

I've seen that an old LP of yours from 1987, All White People

Look Alike, has recently been re-released on CD. I've seen the title

track being described as "a musical manifesto on race, conformity

and (pre-internet) mass culture". Would you mind elaborating?

I'll send it to you. You just have to hear it. It's 20-minutes long,

with many sections but no breaks in between, each goes seamlessly into

the next. It ends with a long crescendo under a spoken word rant that

talks about race and culture and many other things.

In a few Internet Forums I've read some threads about musicians

of the late 60s/early 70s reacting to the Vietnam War and the sociopolitical

turmoil of that era, while nowadays there's not much activity going

on. I know it's a very complex matter, but what's your take on this?

I think probably there is just as much political music as there was

in that era. I think most of it is kind of marginalized by being un-inspired

and by being associated with un-inspired music. There's a lot of well-meaning

but poorly crafted and just not very catchy political stuff. People

find other ways of expressing those things. Also, it alienates lots

of listeners. Particularly in the US.

But that said, there is an amazing amount of social commentary in

hip hop and country music. I mean, country music has become quite adept

at really political propaganda. 90% of it is right-wing. But I see room

for left-wing propaganda in country too. It's something I am working

on. I just wrote a country song called My Country. It is about the things

I admire about my political heritage. In answer to the narrow bigotry

that is starting to propagate from country radio.

Hip hop is full of commentary, very specific cultural stuff, usually

African-American specifically. And a lot of it is bullshit, as far as

I am concerned - a very crass view of human nature, and therefore, a

narrow view. But it is very vibrant.

Why hasn't someone come out with a song, US out of Iraq? I don't

know.

I guess there is something embarrassing about being so "on the

nose". Pop songwriters struggle to make something that is of the

moment but also in some way universal. There has to be a twist of some

kind.

Good question.

©

Beppe Colli 2004

CloudsandClocks.net

| June 11, 2004