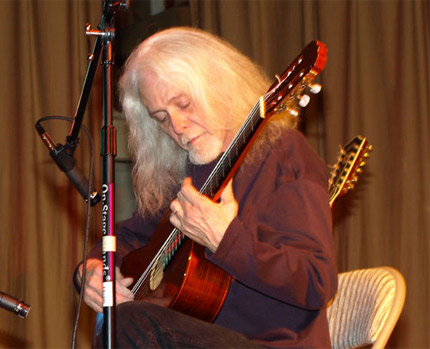

An interview

with

Jim

McAuley

----------------

By Beppe Colli

March 19, 2009

Having listened to it thanks to a fortuitous

combination of events, I decided that I liked the album of duets by Jim

McAuley titled The Ultimate Frog in a way that's quite uncommon these days,

the album being a fine mix of music languages that I recognized as known

and items that were unusual enough to keep me guessing about what was coming

next (which to me sounds like an acceptable definition of "progress

with chances").

Seeing that the artist's e-mail address

was there on the CD cover, I decided to get in touch (what could I lose?)

asking him for a chat, and luckily McAuley said "yes".

After reading a bit about Jim McAuley's

life in music, my problem was not "what to ask?", but "where

do I begin?". Readers will have to decide whether I solved that particular

dilemma in a way that can be regarded as satisfactory.

The interview was conducted by e-mail,

during the first two weeks in March.

Your recent album,

The Ultimate Frog, features four quite different pairings, both in terms

of instrumentation and musical approach. What's the rationale behind

your choosing these particular players - and performances, of course

- to present as a whole?

This project definitely

evolved in stages. In 2002 I had the incredible honor &

pleasure of recording some duets with the free-music legend Leroy Jenkins.

We had a CD's worth of tracks, all totally improvised. But at that time I

was in the midst of recording my solo CD - Gongfarmer 18 - and was devoting

my energies to finishing that and seeking label interest. When the solo disc

was released in 2005, I revisited the Leroy material and realized that as

much as I liked the idea of a totally improvised album, the pieces could

have even more impact when "framed" by more compositional material.

Obviously, I am not a hard-core improv purist! So I contacted bassist Ken

Filiano. I've always loved the scope and musicianship of his playing, plus

he can swing as well as get deep and soulful. After our sessions, things

started getting out of hand!

It occurred to me that

my most successful and ecstatic moments of ensemble improvising have always

involved one of the Cline brothers. Never both, and never in a duet format.

So maybe it was delusions of grandeur, but if this was to be my duet "statement," why

not include the two musicians I most admire and connect with? So I recorded

with Alex and Nels in 2007 - everything from totally free improv to actual

chord changes (a first for me)! Naturally, I now had tons of material to

choose from, but I felt if I could sequence it effectively, it could be

viable as a 2-CD set.

Some of the performances

are obviously improvised - some even being titled as such. But I'm curious

about the amount of preparation - if any - in some duets, especially

those with bass player Ken Filiano.

The pieces titled Improvisation

are all free duets with Leroy, numbered according to the order they were

recorded. Ken and I had a short rehearsal before our session. I had prepared

some ideas - riffs, tonalities, general roadmaps - but nothing too specific.

For instance, Successive Approximations is totally free, whereas The Zone

of Avoidance is based completely on the E melodic minor scale with a chord

sequence as the "head".

I'm curious to know

something about this "prepared marquette parlor guitar" - I

mean, is it marquette, or Marquette, a brand? What's special about it?

It's very special personally

because it was my first guitar. It came from the basement of a family friend.

I've never been able to dig up any information on the brand, but I'm guessing

it was one of those generic instruments sold in department stores in the

30's-40's. It's small (12 frets to the body) and has the slotted tuning

gears reminiscent of the early Washburns. I've always loved its plunky

sound and started preparing it when I joined the Acoustic Guitar Trio (with

Nels Cline and the late Rod Poole). Incidentally, I consciously choose

to limit my preparations to typical guitar accessories: picks, capos, tuning

forks, slides, etc.

I see you also used

the Marxophone (whose sound is familiar to me since the days of The Doors'

first album, though I didn't know what it was), but I can't seem to decide

where it is here - maybe on Froggy's Magic Twanger? Or are those prepared

guitars?

The Marxophone is a

novelty instrument that was sold door-to-door in the early 1900's. It's

basically a keyboard autoharp or zither. I use it on Froggy's Magic Twanger

(retuned to the two whole-tone scales). On that track Nels is playing two

prepared guitars on his lap, similarly tuned, using his signature egg whisk

as well as slides, etc.

If my info is correct,

by the mid-60s you were a grown man. So I'd like to ask you a few specific

questions. Were you familiar with the work of, say, Dave Graham and Bert

Jansch, in the United Kingdom, or people like Robbie Basho and John Fahey

in the United States? Talk about this.

I was definitely listening

to Bert Jansch, John Renbourne, John Fahey, Robbie Basho and Sandy Bull

in the 60's. I became aware of Davy Graham much later. I was attracted

to the eclecticism and integrity of their music as much as their obvious

virtuosity. It's only recently that genres have begun intermingling again

(post-modernism?), which made my music - which has always incorporated

classical, jazz, folk and blues elements - more in keeping with current

trends.

Listening to music

from the 50s and the 60s what I hear - among many things, of course -

is a sense of place, of the music having a specific flavour emanating

from a certain place, maybe I could call it "regionalism".

Do you think it existed, then? What about today?

Though much of the regionalism

of the 60's - the "San Francisco" sound, etc. - was essentially

a marketing tool, there is certainly a grain of truth to the concept. The

East Coast blues sound of Mike Bloomfield or Paul Butterfield were distinct

from the West Coast styles of, say, Canned Heat or Taj Mahal. At the time,

I was especially enamored of the LA folk-rock-pop scene centered around

the Byrds, Love, Brian Wilson and so on. Today, though it might still be

meaningful to talk about "British non-idiomatic improv" or

"Norwegian death metal," these labels are more relevant to die-hard

fans than to the general listening public. It becomes somewhat meaningless

to discuss "regionalism" in a day of international collaborations

via the Internet, for instance. I personally prefer to listen to music with

no knowledge or expectations regarding its origin.

Talking about John

Fahey (I've read you were signed to Takoma, but nothing ever came out):

Were you surprised by his sudden surge in popularity before his death?

I mean, at one point he was quite obscure.

I secured my contract

with Takoma through a demo that included slide blues, gospel tunes,

Renaissance dances, a Van Morrison cover, Round Midnight and some bluegrass.

So they were quite open to my eclecticism. Fahey's approach was much more

focused, but still found room for ragas, sound collage, blues and country

within a very personal style. Yes, I was quite surprised to see his picture

on the cover of the Wire, but I suspect his late-life popularity was due

in part to his cult status, which was a result of his initial obscurity.

Had he been widely popular in the '60's, I think he would be viewed differently

today. In any case, he was a truly gifted and unique artist throughout

his career.

In the 60s you worked

in the studio with Don Costa, alongside people like Tommy Tedesco. Do

you think that the absence of the "human element" that was

prevalent in those days makes today's listening to mainstream music a

more sterile proposition?

If you're referring

to the use of synthesized sound, a resounding "yes"! But isn't

this "sheen" - the precision of the sound - part of the appeal

of pop music? The human element lies more in the vocals and lyrics today.

If you're referring to the post-modern notion of sampling, I think the

focus shifts to the ingenuity & musicality of the mixer/producer. Hence

the popularity of re-mixes. We have become fascinated with the infinite

possibilities of combining sounds rather than with the sounds themselves.

And the samples themselves trigger emotional resonances for those of us

old enough to know their origins!

In the past, groups

like Led Zeppelin functioned as de facto popularizers of

"minority genres" that mainstream audiences didn't really have

any easy way to access. Do you think this role still exists? And what about

a thirst for new things in music on the part of the audience?

In my youthful "purist" days,

I was deeply offended by what I perceived as Zep's ripping off of blues

artists. (Strangely, I've come to appreciate them more as I get older.)

But the practice of appropriating minority genres and repackaging them

as "new" continues to this day, and it still feels more like

exploitation than popularization. And with the easy access of the Internet,

there's no excuse for not seeking out the originals.

As far audience appetites

are concerned, I have noticed a definite shift in emphasis from the "familiar" to

the "exploratory". This again is a result of the Internet's democratization

of music. The mainstream acceptance of "world music" is another

sign that some listeners today seek unfamiliar sounds, as opposed to homogenized

Top 40 fare.

What's the most important

musical lesson you ever got? I mean, were you to choose just one.

It came from clarinetist

John Carter, whom I consider a true musical genius of improvised music.

I call him my mentor, even though we had just a few formal lessons together.

The lesson he taught me was to devote my practice time to the act of improvising

itself, as opposed memorizing scales and licks. This is really difficult

for an aspiring jazz musician who wants to develop his

"chops." You are fighting the natural inclination to develop and

refine your ideas. Even in free music (for me at least), it's hard to resist

defaulting to some lick that sounded so cool the night before - which never

works because context is everything. I find that my best live performances

are those where I can follow the music wherever it may lead without regard

for pre-arranged material (what John called "back pocket material").

Nowadays, the Internet

makes it quite easy for an "obscure artist" to be found and

listened to. Unfortunately, a lot of people have developed the annoying

habit of downloading stuff without paying for it. Discuss.

I have many (sometimes

conflicting) opinions on this subject, but, overall, I think the benefits

of the Internet's democratization of music outweigh the inequities inherent

in downloading. At least in my tiny corner of the music

"business," no one expects to profit financially through their

recorded efforts anyway. And I celebrate the demise of corporate domination

of the record industry; they never properly compensated their artists either.

Possibly some fair model of distribution will emerge in the future. As for

now, I'm just thrilled that my music is available to anyone who's interested

in listening.

Any future plans

you'd like to share?

I have no desire to embark on another full-fledged

studio project any time soon. Possibly I will release some live performances

and/or home recordings in some format or other (incidentally, you can hear

some of my "home practice tapes" at longsongrecords.com). My

current focus is on developing and performing new material. I am playing

a couple festivals next month, and there is talk of some solo dates this

summer. I am also hoping that the duets album will open the door to future

collaborations and musical partnerships.

© Beppe Colli 2009

CloudsandClocks.net

| March 19, 2009