We Love

You

----------------

By Beppe Colli

Aug. 18, 2017

On June 25th, 1967 the "experimental" TV broadcast Our

World, which for the first time linked 25 nations live via satellite, for an

(estimated) audience of more than 400 million people, went on the air, in

glorious black & white.

Given the great variety of languages spoken

by those who were expected to watch the program, U.K.'s BBC asked the Beatles -

at the time, the most popular artist/group on Earth - to perform something

whose message could be easily understood by all.

John Lennon submitted the new song All You

Need Is Love, which the Beatles performed (for the most part) live on that date

and which (with just a few overdubs) became the group's next single (released

on July, 7th), and, in a short while, the unofficial worldwide hymn of that

year's "flower power".

On August 18th, 1967 the Rolling Stones released their brand new

single, We Love You. Here one has to quote John Lennon, when he said

"Whatever the Beatles did, the Rolling Stones did too, six months

later."

One could say that, in this case, the

Stones were only partially culpable, since in the year 1967 - and during that

season: the "Summer of Love" - "flower" and

"love" were quite common words.

But nobody had any doubts about what the

message was. When introducing the Stones' new single in their quite influential

and trendy radio program Bandiera Gialla, Italian radio personalities Renzo

Arbore and Gianni Boncompagni told their studio audience (I clearly remember

Gianni Boncompagni's voice speaking): "Guys, the Rolling Stones love

you!", the audience going "yeah!".

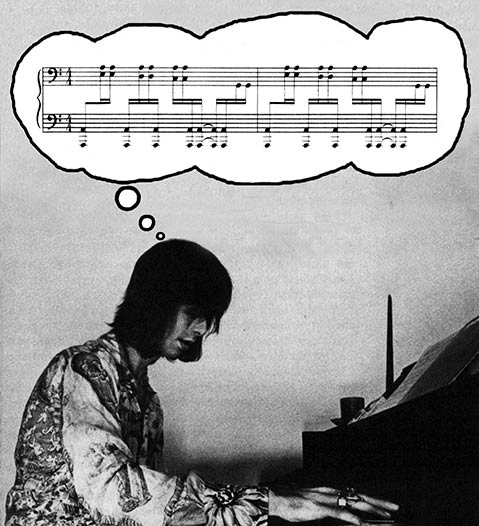

But the single sounded like a very strange "love message",

starting from the very beginning: heavy footsteps on a hard floor, heavy

cell-doors clanging, and being shut - a scene one clearly remembered from many

movies - and then, a claustrophobic-sounding piano riff, a circular phrase

which sounded as if in search of a way out. Some electric bass

"slides" only added more mystery to the mood. Then, a chorus of impossible

falsettos - at the time it was a well-kept secret, but while recording the song

the Stones got (more than) "a little help from their friends" John

Lennon and Paul McCartney. It was at that point that the song really took off,

the vocals suggesting a dream-like scenery over a strange orchestral

background, with loud drums keeping time.

A vocal figure singing impossibly high

notes, which to me sounds as being closely related to the one coming after the

last line of the bridge in A Day In The Life - "(...) and somebody

spoke and I went into a dream" - takes us back to a nightmare - those

clanging doors again, that piano riff - we try to escape, with the resolution

in the bridge getting very strong support from the drums' dynamite hits:

"We don't care if you hound we/And lock the doors around we" (...)

"You will never win we/Your uniforms don't fit we", which ends

stressing words that appear as innocuous, "Of course, we do".

And so, We Love You appears as a unique

specimen in the rock canon, combining the Beatles' melodic meticulousness and

the Stones' sonic braggadocio.

It was "peace & love" time in London, but also a time

of celebrities being arrested. This is the starting point of a

"confrontation at close distance" between the "popular

press" - here are three words that best qualify their attitude when

describing those artists'/musicians' mores: "prurient, voyeuristic,

gross" - and the "new people".

So it was with great surprise that, on June

1st, a Leader by the Times editor, William Reese-Mogg, asked whether the

proposed sentence for the charges facing Mick Jagger - possessing four tablets

of amphetamines legally purchased in Italy - revealed an "ad

personam" hidden motive.

The Leader appeared under the title WHO

BREAKS A BUTTERFLY ON A WHEEL. Here is the closing paragraph:

"There are cases in which a single

figure becomes the focus for public concern about some aspect of public

morality." (...) "If we are going to make any case a symbol of the

conflict between the sound traditional values of Britain and the new hedonism,

then we must be sure that the sound traditional values include those of

tolerance and equity. It should be the particular quality of British justice to

ensure that MR. JAGGER is treated exactly the same as anyone else, no better

and no worse. There must remain a suspicion in this case that MR. JAGGER

received a more severe sentence than would have been thought proper for any

purely anonymous young man."

The Stones shot a promotional video, which

in part re-enacted the famous Oscar Wilde trial of 1895. But the producers of

Top of the Pops refused to air the video, as "not suitable" for their

audience.

The opening piano riff was performed - and, I think, composed on the

spot - by Nicky Hopkins, who had already contributed to recordings by such

groups as the Kinks and the Who, and who in a short while would became an

important addition to famous albums by the Rolling Stones, Jefferson Airplane,

and the Who (and let's not forget his electric piano - a Wurlitzer? - solo on

the Beatles' Revolution).

We Love You - alongside the album the

Stones would release at the end of that year, which will be immediately mocked

for its "Beatles-related" cover, coming six months after Sgt. Pepper

- is the high point of the musical contribution of Brian Jones, the group's

former "blues guitarist" turned into a not-very-disciplined, but

highly effective, multi-instrumentalist. His "Arabic"-sounding

mellotron - showing the fruits of his trips to Morocco at a time this stuff had

yet to turn into a cliché - coupled with those drums represent mayhem after

words had ceased sounding.

Readers will have to decide for themselves

if the last chord sounds like a guffaw.

(Talking about "a song's last

chord": What about the one that ends Traffic's song The Low Spark Of High-Heeled

Boys?)

© Beppe Colli 2017

CloudsandClocks.net | Aug. 18, 2017